In Conversation with Luke Temple

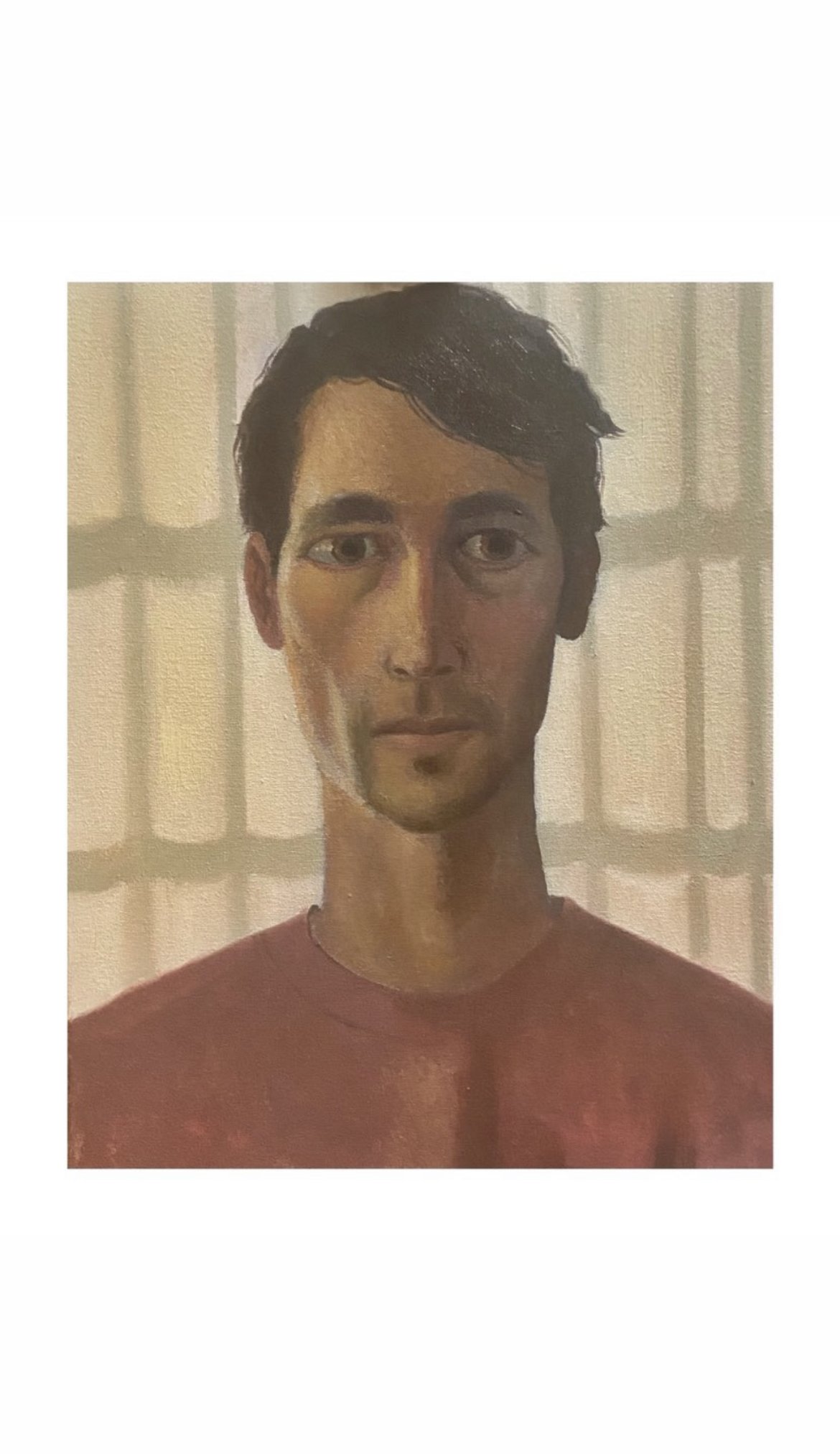

Sitting in a chair by the entryway facing into the apartment, I am still and look straight as Luke Temple begins sketching the outlines of my face. Mid-day sun glows behind me through a large window veiled by a curtain. Last summer, I responded to Luke’s post about seeking people who would be interested in sitting to be painted, and suggested we do an interview while he worked.

Luke told me that he’s always had a knack for drawing people. A ‘talent for rendering’ as he put it. Recently, Luke has organized a number of figure drawing sessions open to people in the community, and it’s been well-received. No frills or themes, just a model and a place to draw them.

“Art is something I get to in between musical projects,” Luke said. “It’s probably something I have more of a natural aptitude for than with music, like on a technical level. When music takes over, visual art tends to fade away until the musical project is finished, and in the interim I'll do more visual art. But it’s never the other way around; visual art never takes me out of music. At least that’s how it’s been historically.”

All photos by Charlie Weinmann

What do you enjoy about figure drawing?

I’m just really comfortable drawing. I’ve just always done that. I think there’s, apparently, a lineage of portrait artists in my family on my mom’s side. So, maybe it’s just in the genes.

When did you start?

I started when I was a kid, I guess, drawing stuff that kids draw like superheroes, but always oriented around the human form. As I got older and went to art school I got more serious in a fine art kind of way. But it’s always been my sort of knee jerk go-to with visual art.

What was your mindset when you moved west [at 19]?

I don't really know, I just wanted to get out of where I grew up. I didn't really have the mind to go to school yet. I grew up in Massachusetts, and Seattle was about the farthest point in the continental United States from Massachusetts, so that was a big deciding factor.

I think back then, it was the 90s, so the grunge thing had happened there, which was a big thing for me. It seemed like a city where I could experience both urban and rural and wilderness. I remember seeing that movie, Never Cry Wolf, and I think the guy was in the Cascade Mountains or something – that was a big attractor to the northwest when I saw that movie.

So at that point had you been writing music?

No, I hadn't been writing music. I played bass back then and just jammed with friends – my best friend Peter and his cousin Justin. Peter played drums and Justin played guitar and we’d just jam. I was sort of decidedly ‘free’ – I didn't want to learn songs, I didn't want to learn covers, I didn't want to do any of that. I just wanted music to be this totally improvised thing. So I just played in that context, even at the point when I moved to Seattle I was playing in that way, mainly by ear.

I ended up in northern California after Seattle and had sold everything I owned because I was so broke.That was around the time I started just playing guitar – proto songs, nothing really serious. Then I went to art school. Then after that I moved to New York, which is where I started writing songs. I lived all over the place there. Greenpoint, Chinatown, Bushwick. […] 16 years in NYC.

Could you talk about the earliest stages of your musical career?

I was living in Seattle again, this time with a partner. I made a record with a label and then moved back to New York. I had a lot of delusions of grandeur – hoping to become famous. On one hand, I had this over-extended version of confidence and I also had an extreme insecurity, both of which have evened out as I've gotten older. Both are in an appropriate place within me now compared to back then. I don’t think I really understood what I wanted yet. I was still listening to what other people were telling me a lot. How I made that first record kind of got out of my hands and I sort of regretted it. It was a process of coming to terms with doing what I wanted to do over the years. It's been like that ever since then.

And that feels good and natural? Like a progression?

It’s hard to say if it feels like a progression. Sometimes it feels like an opposite, like reductive. I guess progression insinuates the building of something, like hierarchical, going from bad to good or something, or like getting more tools along the way. My feeling is that it’s stripping away unnecessary things and coming to terms with myself and what I'm good at, and letting that be. Your skill-set improves overtime, as it does, because you’re practicing your craft. But that just happens. I'm not someone who sits and practices every day, but I've just written a lot and have spent a lot of time playing. My skills get better. In terms of the creative direction, it’s more a feeling of going, not backwards, but getting to the truth of it.

The truth of what?

An uncompromising feeling of what I’m saying musically is really me, is really coming from me. We’re a product of our environment, of course, so we can't help but be influenced, and we’re also dependent on our environment. We don't exist in a vacuum, I understand that, but there’s a process that I still go through that can be a struggle sometimes, where I'm subtly wanting to impress. I think I want to impress myself, but sometimes I’ll realize I'm just wanting to impress other people, and if I sense that I'm going in that direction, I just notice it. The competitive spirit has delivered a lot of amazing art. Even within that, there can be some soulful, impactful art made. I think The Beatles, the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones were probably all competing with each other to some degree, wanting to feel they were supported and respected by their peers and all that stuff. But, that needs to be at an appropriate amount. When it’s the leading force, it can be the cart before the horse…

I guess it's coming from a place of, ‘this is who I am, unedited, this is what I’m wanting to say.’ Maybe it’s scary or vulnerable, which I've learned can be a sign that it’s good, if it feels uncomfortable in some way, and that can exist in tandem with still, the subtlety competitive aspect of me existing, I guess, in the marketplace, or social acceptance. So I think it's coming to terms with all of that stuff. It’s outward versus inward and where you’re working from. – They both need to be there to some degree. Something like external concerns aren't just egocentric and bad, there’s something there that’s helpful.

Have you ever been religious? Or are you?

I guess so. I have a religious spirit. I’ve been, I guess, a ‘sidelines’ Buddhist, and do Runyon analysis.

Do you meditate?

Yeah, I do. In the morning. I write. I wouldn't say I have the strongest practice. I have a very busy mind that I don't feel like I'm able to really wrangle, and that might be something I need to accept.

Is that something you’ve realized recently?

No. But, I guess the idea of any spiritual discipline distilled down to its essence is about awareness – coming from the more objective witness in yourself. Like ‘know thy self’ – it’s just you’re coming from that – when you meditate there’s that clear awareness that can see, ‘oh, I am thinking this,’ or ‘I am feeling this.’ Even in the most horrendously emotional upheavals, there’s still a part of you that’s like, ‘I am devastated,’ you know? I think it’s just identifying more with that part of yourself so you can stay at the center. I guess that’s the center – the undefiled, kind of clear mirror of awareness. The world of phenomena, of passing and arising, and passing away, which includes your mind. We just can't measure thoughts as a quantifiable thing, but I'm sure we will at some point. Emotions and thoughts are physical to some degree. I think we like to think that our thoughts and our emotions are closer to the spiritual side of us, but it’s all … what’s not spiritual? Matter is spiritual. It’s all the same thing, just Mandelbrot. The Mandelbrot Set: it’s like a fractal, you can go endlessly inward and it always ends up repeating itself in a more intricate, smaller dimension, or endlessly outward.

Emotions and thoughts are like the same thing as clouds passing through the sky, to put it crudely.

Maybe the thing about meditation practice is realizing that. It’s not about pacifying your mind, necessarily…I don't know.

Some people have some really profound experiences – the Zen term for enlightenment is sumat. They have that experience where they enter that stillness and they have that sense of oneness with everything – but I’ve never experienced that.

How long have you been practicing meditation?

10 years.

And your practice involves writing?

Well, sometimes. The kind of meditation I like to do is ZaZen, which is the simplest kind of mediation: You sit and follow your breath. There’s no visualization, there’s no goal, it’s just being with yourself and just watching all of your inner, and to some degree, outer phenomenon, rise and fall away. You sit with your eyes half shut, and with your hands in what they call mudro which has your thumbs together just enough where you could hold a piece of paper. If your thumbs separate, you know you’re spacing out, and if they come together, you know you’re over concentrating. You focus on your breath going down to your lower abdomen, and try to count to ten without a thought coming through, which rarely happens, and when a thought comes through, you go back to one. It’s really a somatic thing, about getting in touch with your body and sitting with what’s real, and not abstract. I think we identify with our thoughts a lot more than we identify with our physicality. Our thoughts are just springing up, like little messengers, projections from our unconscious and our shadows that are really fascinating, but also we can probably end up relating to that more than we can with the physical reality of our lives. So in some ways it’s really not spiritual – Zen is like, when you walk, just walk, when you wash a dish, just wash the dish, when you are talking with someone, practice listening.

… It's fascinating stuff to me – the frontal cortex, that creative aspect of a human being, that abstract thinker, the problem solver, the ability to think of something outside of your immediate environment to fix a problem has brought us to the point where we’re at. Animals have sort of a more proto-version, maybe. We’ve certainly excelled at that. It’s our gift but it’s also our problem. We forget how to just be ourselves. When you look at a horse, when they’re not galloping and they’re just in the stable, staring, just completely still, they don't have any issue, or a guilt complex around being that, just being a horse, that's it. I have a sense that most other animals don't have an issue with just being themselves in that way. We do though, because we have these abstract ideas for what it means to be us and what it means to be successful. But they’re just residue, from a Jungian standpoint, they’re the buildup of the collective unconscious from all of our industriousness over thousands of years.

All of our thoughts are these little energy patterns that have passed through us ancestrally. It’s as if they’re thinking us rather than us thinking them. I’m getting pretty out there. I’ve just been reading a lot of Carl Jung.

You know the word archetype – Jung believed that through these concepts, like the concept of mother, for instance, there’s instincts, you’re born of a mother – that's a thing that didn't need an archetype to exist, it's just real. We have the feminine and masculine – the female version of the animal, in the mammalian world, bares the children, but since the beginning, since we’ve had this way of thinking and creating images, we’ve created a symbol of mother also in our minds. And that symbol has generated all of the intricacy of 200,000 years of evolution, or even longer, from when we were some mole creature of something. That symbol in our mind has taken the shape of this mandala image of all the different layers of what mother means. And so when we think of mother, it’s enmeshed with all of that from the beginning of time. It’s passed down through our genetic coding and it arrives in our life specific to our environment of the moment. There’s a myriad of different heads on the same idea. So that’s a grand archetype, the mother. And then there’s the simplest things, like the idea of what it means to walk, for instance, is subtly an archetype.

We live in these concepts. In a way, when you figure draw, when you look at something you have to get over your projected archetypes and just see things clearly in order to get a good result. If you’re looking at the eye as an archetype eye with all of that abstract consideration of what you think an eye is, you’re probably not going to draw the thing in front of you very well. But, Jung will say that the archetype is real, it’s a real energy in the matrix that exists, in our nervous system and in our brain. That’s the most fascinating thing.

Then he has this idea of ‘the shadow,’ which is that we’ve adapted these archetypes in our life in a way that suits us based on our environment and our conditioning. And there are certain more wild aspects that still exist in us, from animal times, from more instinctive times, that are not appropriate. So we shove them away, and they exist as our shadow – they exist in the unconscious. They can’t go anywhere so they inform us as we go through experiences – they come up in experiences of tension, or experiences of anxiety or neuroses.

[Jung’s] whole thing is what he calls individuation, which is the path of becoming the most you that you could become. It's not only about only becoming good, it’s about being able to hold the tension between the opposites, the tension between what you ideally want to be, but then also being able to exist with the contrast of your darker aspects – just accepting the two and being able to live with the tension. It's the baby with the bathwater – you get envious or you get jealous, you get angry, and you think ‘oh, i didn't know I was such a terrible person.’ But in the sense that the worst of the worst exists within all of us to some degree. It's like passing through that is the difficult journey – the sort of hero’s journey, as it were.

I think that practicing spirituality is practicing awareness. If you’re letting things rise and pass away, inevitably you’re going to leave room for the darker aspects of you to come to the fore. And I think that’s where that impasse happens – that difficult, sort of desert moment.

And this is something that happens consistently throughout a lifetime…

Jung was active at the turn of the century, so it was a different time – but he’ll say that there’s the phase of youth where you’re completely dependent on your environment – dependent on your mother, the strongest archetype that exists. You’re at the whim, you’re unfettered emotionally speaking, you’ll just experience whatever passes through you. You haven't socialized to the degree where you would understand if something was inappropriate. You’re pure, in the garden of Eden kind of. That’s the parable of that time. You’re naked, you’re part of everything, everything is part of you. You are taken care of.

Then there’s the adolescent phase where you become socialized, you have to go school, you have to understand that you are an autonomous individual and that your actions have consequences, and there’s probably some sort of phase shift that’s difficult. Especially when you’re a kid – when kids start going to school they don’t have moral sets yet. They’re all these sociopaths just hanging out with each other and pushing boundaries.

And then you leave your home somewhere in your 20s and then there's this real consideration of ‘who am I in the greater world?’ I think for me, and I can only speak for myself, that was more of an emotional, like coming to terms emotionally with where I fit with society.

Then there's the phase of responsibility, the more inward looking. A lot of people in their 20s are in their existential phase. And then your 30s come around and you all of a sudden find yourself in a career or you’re closer to actualizing yourself in the external world - maybe you have children, maybe you have a spouse – then all of a sudden you’re back out in the external world as it were, just providing and being responsible, and there’s just no time to think about anything else.

And then midlife, your kids leave and you’re left alone, and you sink into that. That's the midlife crisis point where the ground falls away from you. You realize that you can't take anything that you’ve garnered for yourself, that you've amassed in order to feel satisfied – it won’t [satisfy you].

There’s emptiness involved in life at all points, there’s nothing solid. Nothing is permanent. The midlife crisis leaves someone trying to make up for that sense of loss, or sense of impending death. Or it thrusts someone into a new spiritual life. Or they get a new car or a new, younger romantic partner.

Do you see yourself anywhere in this spectrum?

I think I'm in the midlife crisis point. I have a lot of joy in my life, too, but I'm not a lot of things. I think not having a family is the thing that I’m wrestling with. That's the biggest thing for me, and whether that’ll happen or not. It's scary getting older and looking into the future and wondering if I’m going to be alone when I'm 70. I had never thought about that before. I have my own version of it.

How old are you now?

47. … I think I'm also looking at it like, this year has been really hard in that way. I got out of a relationship I thought was solid but wasn't. I also got sober this last year. So it's been hard, but I guess I'm taking it as a gift in a way too. I'm doubling down on the work on myself. Going to therapy, not drinking, trying to be good to myself. Finding ways to be more involved with community – where I put out that energy that I would otherwise want to instinctively put towards a family, into community.

Jung’s perspective sounds a bit sad to me.

I think that it is, but it’s also necessary. In Buddhism the first noble truth is that life is suffering. That sounds really dour. But what it means is that, roughly, is that attachment to the transience of life is suffering. What we love disappears. There has to be an equal amount of loss for gain, it’s the law of displacement of energy. There has to be an equal amount of darkness for light – light can’t exist without the darkness. Suffering is part of the joy of life. It's almost as if suffering is the thing we’re trying to get away from the most. It's the monkey on our back. But it's the most poignant aspect of life. It's like happiness, being joyful and simple and free and happy almost feels more like a resting state. That place, in my experience, is like the resting state of life, the energy of the universe is this joyful kind of thing, there’s nothing existential about it, there’s not a lot of meat to it. It’s like a clear, simple, kicking the can down the street … sadness – the depth of sadness and pain, there’s so much intricacy to it. It's like vines growing in the jungle or something. There’s humidity and there’s denseness, and so many images, it’s like intrinsically human.

There’s something about it, there’s something about the struggle of life that’s bound in sadness, in a sense. It’s just an energy – if you look at it that way, you just see it as part of life, this suffering. Then there's nothing depressing about it. If we're trying to get away from that feeling, then it’s depressing. But if you just look at it as the other side of the coin, it’s like the price we pay for being alive. And we’re doing everything in our power as civilization to sort of thwart that from being the reality. And it’s really causing a lot of problems. Those darker aspects of life, those darker archetypes, suppressed to the degree that we do suppress them, come back in the form of things like Hiroshima. They’re not around in the day-to-day. We don't exercise that darkness. Maybe more primitive peoples did exercise that darkness on a more regular basis, for better or for worse. There were unspeakable things being done that would never be allowed in our society today. But it's almost like the idea of a sacrifice is a ritualistic offering – an acknowledgment of life, that maybe pacifies that energy from getting into more inappropriate spaces.

So anyway, the midlife crisis, or any kind of lack of life energy or feeling unfocused – that can be a gift in a sense, because it puts you in contact with something that needs to be expressed.

That has been my experience in the past year or so, and it’s been hard. Because I always just want to be kicking ass, or being my best self, ‘living my best life’ … That makes me really nervous when people speak like that.

For whatever reason it’s like the most interesting thing for me to do – it seems like an internal experience. I'm an introverted person. An introvert experiences the world from a more subjective point of view, from a more internal point of view. That's all you know. But I think if you were zapped into an extroverted experience, it would be profound, the difference.

[Introverts] are what they’re doing. They are all of their exercises with the world around them. An introvert is always, ‘this is how I’m relating to this thing,’ which isn't necessarily egocentric, it’s just that the outward and the inward are both real. Neither is false.

But the inward types tend to be the people that are more attracted to spirituality or maybe the arts too, I don't know. But it's certainly something that our culture is becoming more extroverted. It’s championing only extroversion, really. There is not much place for an introvert in our world of ‘living your best life,’ and getting what you want, ‘optimizing your performance’ … It's hard as an introvert to just do something because they are always aware of the different types of relationships they hold with things. It's hard to just do without thinking about it, thinking about the implications, or considering my relationship with it. So a lot of times it leaves me in a state of not doing anything, in a stalemate.

I've been there! Do you ever feel that way when writing songs?

Yes. It’s hard, sometimes it flows. It's hard though. It’s always been hard. I have moments. I'm in a dry spell right now, but I think because I just did two records, the Art Feynman and the Cascading Moms record, so I think I just have to recharge for a little while. I don't know what kind of direction I'll want to go in.

Do those records have very different identities?

Yeah, the Art Feynman record has the most clear identity of anything I've ever made. I think it has a lot to do with that group of people [who helped make the record]. We played those songs enough before we recorded where everyone had their idiosyncrasies in relation to the music in tact, so it just really feels like a well-thought-out thing. I guess the identity, from a genre standpoint, it’s like funky post-punk. Like, I don't know, Ian Dury, he did that song “hit me with your rhythm stick, hit me!” … the 80s, Talking Heads, the punk thing happened, and then reggae and African music was allowed to enter into the stream.

There's an angular aspect – a lot of the lyrics are kind of existential … stuff I'm interested in, a lot of anxiety going on in there too. But it kind of has a joyful thing about it too, I think.

Cascading Moms is probably more related to my solo stuff … Kosta [drums] and Doug [bass] just have a strong vibe. That feels like a band, too, in a way.

When do you want to put that stuff out?

Probably Art Feynman before Cascading Moms. The Art Feynman record feels more prescient. I think because I’m still working on it it feels like a character or a voice that I haven't really expressed yet. Or maybe something I've been touching on in the Art Feynman stuff, but it feels more clear with the Cascading Moms record. I'm also interested to just see what it does … it could give me a little second life maybe, I don't know. I haven't been thinking of my records in those terms at all, I just make them and put them out and don’t really worry about whether they do well. But this one I think people might actually resonate with, like a wider audience.

Who is Art Feynman?

There’s a humor, clown aspect to Art Feynman as a character, I guess.

Starting that project through the lens of a character helped me sort of inhabit spaces where I wouldn't have normally allowed myself to be.

And making music that’s groove based, and not having to burden myself with ‘writing the song.’ This guy, Arthur Russell, was a big influence.

Are there songs of yours that stand out as your personal favorites?

There’s a song called “Over The Ocean” on a Here We Go Magic record. I like that song. I like “I'm Gonna Miss Your World” a lot. I like “The Physical Life of Marilyn” a lot. I like “200,000,000 Years of Fucking.” I like “Taking Chances”, “Wounded Brightness”, “Tunnelvision” which is a Here We Go Magic song.

How do you feel about songs of yours that have become your most listened to?

It feels fine. I understand why it is … I hear things in some that I would change. I'm really critical of my stuff. For a long time I would just make records and not like them. I'd be buried in it for so long and, once it’d be mastered, I’d have some perspective and would be like ‘oh no, I lost my way … I got stuck in some kind of minutia and sucked the life out of this.’ And of course, I can't really hear it objectively. I have friends who have said ‘if you’re looking at it that way, it’s just going to be your whole life.’ And I was like ‘no I think I'll get better,’ which helped me feel satisfied. And it’s true, as I've gotten older, I'm liking my stuff more as time goes on, which is nice.

It feels vindicating that I was critical in a way that maybe was helpful. Self-criticism is not always bad.

How do you feel about playing solo versus with a band?

I like playing solo if I’m doing it more intentionally. Sometimes the solo performance will sneak up on me and I'll just do it and sometimes won’t enjoy it. But if I go into it intentionally - ‘it's going to be my voice and this guitar and I’m going to do this thing, I’m going to create some sort of psychedelic experience with just these two elements…’ then I can get into it.

It's terrible, though, when you’re playing for people who are just eating dinner or not listening - it can be awful. I'm very sensitive to that kind of thing. It's hard for me to power through.

Do you have aspirations that are more or less outside of your current reality?

I’d like to paint more, I think. I'd like to paint large paintings of people in scenarios. Maybe more the psychedelic, more surrealistic stuff where I incorporate the realism with the more surrealistic stuff. I still feel like I'm getting some traction, or barely, with visual art. I’m still developing a language. I have a talent for rendering and I can just do that, and I can always paint people, which there is some gravity to, but I think that I’m wanting to say something more than that somehow.